Most summer Saturday nights of my childhood, I snuggled in…

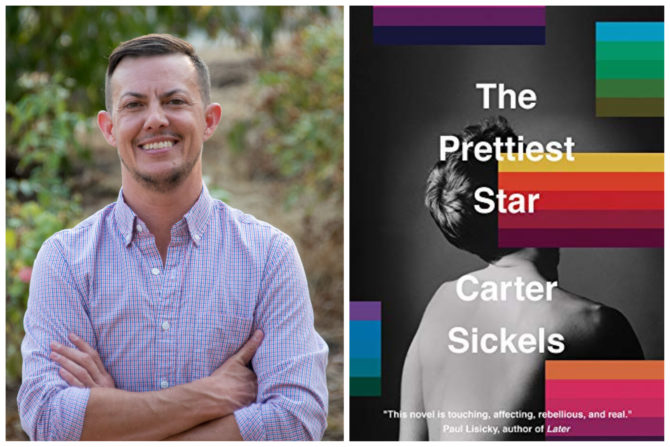

In Conversation: Carter Sickels

In January, as he walked through the crowded streets of Park City, Utah, Carter Sickels’s year looked set. The film adaptation of his debut novel The Evening Hour had just premiered to critical buzz at the Sundance Film Festival. Praise was already rolling in for his second novel The Prettiest Star. Set in 1986, the book tells the story of Brian Jackson, a gay man from rural Ohio who seeks freedom and acceptance in New York City. But after losing his lover to AIDS and facing the prospect of his own death, he returns to the family and place he left behind to confront his past and future.

Earlier this spring, as the country moved into lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Sickels discussed the book in a series of emails with fellow novelist Robert Gipe. In the conversation that follows, edited for length and clarity, Sickels reflects on his inspirations for the novel, the AIDS crisis in rural America, how he conjured the 1980s on the page, when we can expect to see the film of The Evening Hour, and the parallels he sees between our present moment and the world of The Prettiest Star.

■■■

ROBERT GIPE: Why did you write The Prettiest Star?

CARTER SICKELS: It was an idea I’d written down, just one idea of many, for a short story or a novel: an HIV-positive man returns to his hometown in the mid-eighties during the AIDS epidemic. I didn’t know if the idea had legs or not, but I kept coming back to it. I started thinking about Jess, Brian’s little sister, and how it would feel to have her brother come back. Brian’s voice started to speak to me too. Then, I thought about the family and the town, and the stigma surrounding queerness and AIDS. I also remembered watching this episode of [The Oprah Winfrey Show], when I was a teenager, about a gay man who was HIV-positive, and went swimming in his hometown public swimming pool in West Virginia; when he got in the pool, everyone else got out, the mayor drained the pool, and he was barred from coming back. That stuck with me, too. It happened in 1987.

I wanted to tell a story about the AIDS crisis—this time of America that so many young people don’t know much about, this critical moment in queer and American history—and look at it through the lens of rural America.

RG: Tell us about the research behind The Prettiest Star. How did you prepare to write about that time and place?

CS: I conducted a lot of research about the AIDS crisis in the eighties. I read everything from seminal texts like And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts to magazines articles in Life and People. I looked at art from that period, like the work of David Wojnarowicz, and the photographs of Nan Goldin, and watched documentaries and videos.

One particular influence on my novel was [the memoir] My Own Country by Abraham Varghese, about Varghese’s years as an infectious disease doctor in east Tennessee, where he treated some of the area’s first AIDS patients. It’s the only book, at least that I’m aware of, that examines the AIDS crisis of the eighties and nineties in rural America. Varghese portrays the deep isolation people felt, people who often didn’t have familial or community support, or resources, with tenderness and complexity.

I also drew on my own memories and immersed myself in eighties pop culture by listening to a lot of music and watching music videos, TV shows, commercials. The Internet makes that kind of research super easy, but physical objects also hold major memory power. I ordered Sears and JCPenney’s catalogues from eBay, and searched antique and secondhand stores for old copies of TV Guide, and those were excellent resources for transporting me back to that time.

RG: What, if anything, surprised you in your research?

CS: I knew about the cruelty and paranoia toward people with AIDS—parents requiring their sons eat dinner at a separate table, nurses or aides leaving trays of food in the hospital hallways, or parents not claiming their son’s body from the morgue. But, I have to say, I was disturbed to read about funeral homes refusing to bury the bodies. I even read about one place that sealed the body in glass. Were they afraid the other corpses would be infected? That kind of fear grows out of a deep hatred that seemed to be about keeping queer bodies out of every public space, including cemeteries.

Honestly, in all the research, I was more surprised by the small acts of kindness and support toward people with AIDS that I came across. Parents taking in their gay son, or a woman, who, despite her preacher’s hellfire and brimstone sermons, delivered food to a queer couple in town.

RG: What part of the world of this book was the hardest for you to create? What part came easiest?

CS: I grew up in the eighties, so I felt comfortable writing about the time period. The sense of place—in southeastern Ohio—also came pretty easy. What was more difficult was not so much the world, but the novel’s structure. Brian’s video diaries, for example, took some time to figure out how to construct, how to turn something that is so visual into prose. The alternating points of view also presented challenges—deciding when to switch perspectives, or which character would narrate a particular scene.

RG: Are there any analogies or comparisons you’d like to draw between the AIDS pandemic of the eighties and the COVID-19 pandemic? Interesting to compare the reactions to the two pandemics by some of those on the religious right.

CS: This is such a tricky question because right now we’re right in the midst of this global pandemic, and things are changing so rapidly from day to day. It’s important to note that regarding the AIDS pandemic, we were six years into the pandemic and over 40,000 deaths before Reagan ever mentioned the word AIDS to the public. Gay people were viewed as expendable—there were many in the country happy to see that queer people were dying.

I do think, currently, we’re witnessing an incompetent, cruel administration that values the stock market over human lives, and has waged a war on science. It’s also interesting to look at the hold the religious right now has on this country and political leaders, a movement that found its footing in the eighties. Jerry Falwell famously said that AIDS was God’s punishment for the gays, and he played a major role in garnering Christian support for Reagan. Now we have his son, a great friend of Trump’s, leading college students into a mess of COVID-19 infections. I’m sure at some point, if they haven’t already, the religious right will blame COVID-19 on the gays.

RG: Andrew, the gay man who stayed in southern Ohio, says “This is our work now” to Brian’s mother Sharon when Brian comes home to southern Ohio to die. That exchange was very meaningful to me—the way it spoke to the way people have to make their own family, their own community when their birth families and communities reject them. I also love it because it speaks to maybe Andrew’s sense of “missing out” because he wasn’t living in a larger gay community—and how ready he is to assume his place as a caregiver in that larger community. And I love it because of the way it helps Sharon find her love for her son. The world they create around Brian is so beautiful. Anything you’d like to say about how and why you created that space?

CS: Thank you for bringing this up. This was important to me to write, and I hope it resonates with readers. Even if their own families support them, I think queer people understand, collectively, what it means to be rejected by their own biological families. There are the families we’re born into, and then there are families we choose and create. The queer community has been doing this for years and years—redefining families and homes, taking care of each other because our own families or societies won’t. In the eighties and nineties, queers stepped in to take care of their friends and lovers, in ways that most biological families were not doing. In The Prettiest Star, I wanted to show how Brian’s family includes his queer friends and a few members of his biological family. This newly-formed family explores one of the novel’s primary questions: how do we take care of each other? Will we extend our compassion, treat each other with dignity and respect and love?

I’m glad you brought up Andrew, who was one of my favorite characters to write. Many queer people leave their hometowns for urban spaces—for community, acceptance, freedom. But there are also stories of queer people living in rural spaces and those stories don’t often get told. Andrew is a gay man who never left the area, and works at Sears. He doesn’t try to hide his femininity, and Andrew’s mother Janey is very supportive and loving of her son. I wanted to complicate ideas about [queerness in] urban and rural spaces, and about the people who live there.

Andrew creates a shift in the Jackson family dynamics, and destabilizes the story Brian’s parents want to tell about this family. Over time, Sharon, Brian’s mother, who at first couldn’t see Andrew beyond her own prejudices, begins to rely on him and trust him.

RG: There are so many other strong well-drawn characters. We’d welcome any thoughts you’d have to share on the creation of Lettie, Brian, Jess, Sharon, and Travis.

CS: Lettie is Brian’s grandmother. When I started writing Lettie, she drew me in right away—with her dyed black hair and gaudy jewelry. As I wrote scenes from Brian’s childhood, when he went door-to-door with Lettie selling Avon, or twirled around the house singing Dolly Parton, Lettie quickly emerged as the character who would love her grandson unconditionally. As the matriarch, Lettie carries a kind of power within the family, and even within the community, and so her support is significant. I wanted to include a family member for Brian who protects and accepts him. I enjoyed writing Lettie, who brings a little levity and humor to the family unit.

Brian is the main character, and this is his story—but it’s also the story of his family and community. In early drafts, Brian was all rage. But, the longer I stuck with him and developed the novel, he grew more complicated and layered. The video diaries gave me a way to let him speak directly to the reader, and to frame his story in these short sections where he’s at his most vulnerable and honest, but also in control of his own story. Over time, as Brian becomes sicker, these videos start to disappear—and I wanted the reader to miss his voice, to feel that loss, that grief.

Jess is fourteen, and hasn’t seen her brother since she was eight. No one will tell her why he left or why he’s come back. She has to navigate this adult world of secrets and shame and silence. But she’s savvy and sharp, and figures out what’s going on. When I’m creating characters, I try to figure out what obsesses them, their likes and dislikes, their desires, fears, or sorrows.

With Jess, I thought about what TV shows Jess, a fourteen-year-old girl in 1986, would be watching. MTV, of course, and a lot of sitcoms. But when she was younger, what shaped her? Before my family had cable or a satellite dish, we had four channels to choose from. Like most kids from that time, I watched a lot of PBS. In addition to Sesame Street, Mister Rogers, and The Electric Company, nature shows always seemed to be on TV. Nova, Wild America. While I was thinking about Jess’s TV-watching habits, I also watched the 2013 documentary Blackfish, an indictment of SeaWorld’s practice of raising orcas in captivity, and remembered when I was a kid, taking a trip to SeaWorld Ohio (yes, this was a real place; it closed in 2000).

What if Jess watched a lot of nature shows? What if she fell in love with killer whales, the way some girls do with horses? She’s never been to the ocean, and the images on the screen, and all the books she reads about whales, transport her from small-town Ohio to the wildness and mystery of the sea. As I did more research, I started to hear Jess’s voice—and her brainy knowledge of whale facts and details worked their way into the novel.

Sharon, Brian’s mother, presents herself as a woman who’s very put-together, who doesn’t get easily rattled. She keeps her house in order—she’s always cleaning, she likes neatness. And yet, when Brian comes back, that order falls apart; she can’t make this into a neat story. Sharon is grief-stricken but also stuck in her own shame and denial. She’s a character who makes slow but instrumental changes.

Travis, Brian’s father, cannot accept his son’s queerness or that he’s dying—and he retreats from Brian and from the family. By only showing Travis through the other characters’ eyes, his interiority is inaccessible to the other characters and also to the readers. But he also carries around so much guilt, grief, and loss that he cannot face. I knew that Travis would only get one chance—when it’s too late—to speak about his son.

RG: What are your thoughts on this as a novel of place—to what degree did it have to be set where it is set?

CS: I wanted to write about Appalachia Ohio, a place where my grandparents lived and that still feels like home, partly because I haven’t seen it show up much in literature. The setting is rural and isolated, and quite beautiful. Brian wants to see his family, maybe reconcile with them, but he also misses the home where he grew up—the woods behind their house, the hills, the trees.

The time period—1986—is critical to this novel, and in some ways, that’s even more crucial than the place. I wanted to examine what was happening outside of urban spaces—how small towns and rural places were grappling with or refusing to face HIV and AIDS. I think this is a story that is Appalachian, and yet a similar story could easily take place in any rural small town in America—in Oregon or Maine or Nebraska.

RG: You’ve been a part of various different Appalachian sub-regions. What characterizes Appalachian Ohio in your mind? What distinguishes it from the rest of Appalachia in your mind?

CS: I’m no expert on Appalachia, but I do think this is a corner of Appalachia that is often overlooked. Southeastern Ohio borders West Virginia, and it’s a beautiful area of the state. People tend to think of Ohio as flat land, not hills, and typically assign Appalachia only to settings with coalfields and mountains. And, it’s true, Ohiodoesn’t have mountains like most of Appalachia, but the region has faced similar hardships and suffered at the hands of corporate exploitation and greed—the opioid epidemic, and pollution and toxic waste from strip mining and coal-fired power plants. When I was working on my first novel The Evening Hour, I spent a lot of time in the mountains of West Virginia, and much of the place reminded me of southeastern Ohio. The people I met, the culture and language. I hope the novel will be in conversation with other Appalachian novels.

RG: The film adaptation of The Evening Hour premiered at Sundance in January. How did it feel to see your characters and story on the big screen?

CS: It was amazing. I’m so grateful that I had the opportunity to see the film premiere at Sundance, before the world so drastically changed. To see my characters come to life on the big screen—what a beautiful dream. The director Braden King, screenwriter Elizabeth Palmore, and all the talented actors took great care in capturing the heart and tone of the book, and breathed another life into my story. It took years for everything to come together, and every single person worked extraordinarily hard on this film. At this point, the film is circulating in film festivals.

RG: Like many writers with books coming out this spring, your book tour for The Prettiest Star was upended by the COVID-19 pandemic. How challenging has this been and how have you adapted?

CS: In the beginning, it was a major disappointment. I had been looking forward to a book tour that would take me all over the country, and planned to be traveling March through July. So it was very disorienting, as it was for so many of us, when those plans completely fell apart. It was also a strange, slow unraveling. If you remember back in March, which seems like a lifetime ago, most of us didn’t grasp the depth or extent of this pandemic. In March, my publishers and I assumed the readings scheduled for May would still go on. Then, in April, we thought surely I’d still be reading in June. Now, I’ve adjusted and adapted, as most of us have. Though I’d love to socialize and hang out with friends and travel, I’m not planning on doing that for a long time, at least not in a way that doesn’t include social distancing and masks. I’m trying to stay healthy and safe, and doing my part to helping others stay safe too.

I’m incredibly grateful for how bookstores and the writing community have adapted during the pandemic—supporting each other, moving readings online, getting the books into readers’ hands. It’s a testament to how robust the writing community is, and shows how much we need literature and the arts for nourishment and connection. Of course, I miss the physical space of bookstores, but we’ll get back there one day. I encourage everyone to keep buying books from independent bookstores so that we can to keep these businesses alive and thriving.