Met In an orca-colored room, we glare into a jungle…

On Being Still and Knowing

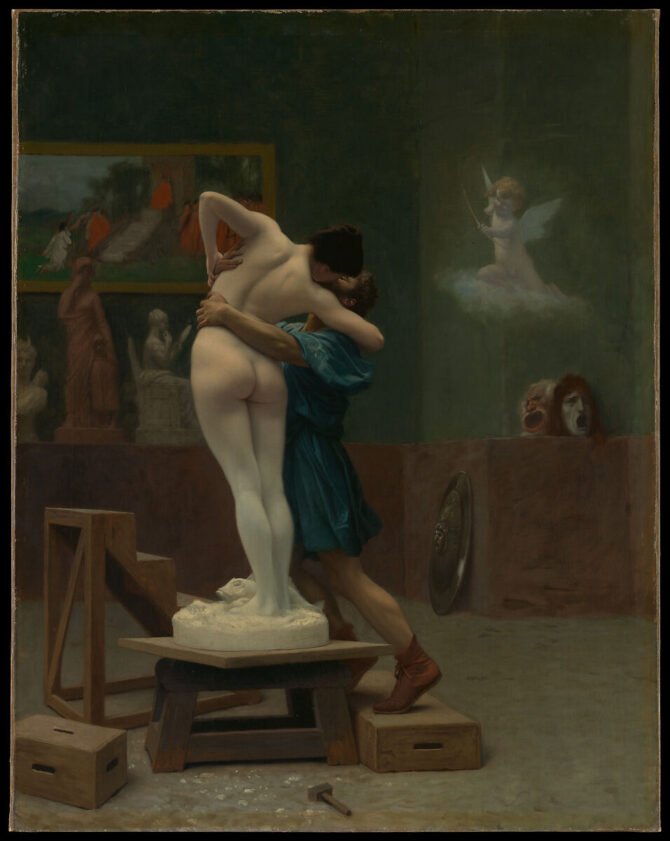

The focal point of Jean-Léon Gérôme’s painting Pygmalion and Galatea (1890) is, undeniably, Galatea’s ass. It is this point on her body, just under those pert cheeks, to be exact, that her metamorphosis from cold white marble to warm, blushing flesh takes place. Standing on a platform in the middle of her creator’s studio, the statue-woman’s pose is full of tension, of muscular energy frozen in time. She leans over to kiss Pygmalion, who rises on his tiptoes to meet her. In the background floats an ephemeral Cupid on the brink of letting a love dart fly.

The myth of Pygmalion and Galatea goes like this: Pygmalion was a sculptor in Cyprus who, having no interest in living, breathing women, sculpted his ideal of one in ivory. He named his creation Galatea, meaning “milk-white woman”. Pygmalion became enamored with his creation, bathing her, dressing her, bringing her trinkets, and gazing at her for hours. He prayed to Aphrodite to give him a woman just like the one he’d carved, and Aphrodite answered his prayer. Galatea came to life, she and Pygmalion had a daughter, and everyone lived happily ever after, as far as we know.

The story became a sort of obsession for Gérôme, who created at least five known versions in oil as well as a marble sculpture in the span of two years. Other versions show up in the backgrounds of his works Working in Marble (1890) and The Artist and His Model (1894)—two paintings that are almost exactly the same painting. Both self-portraits, they depict Gérôme in his studio at work on his sculpture Tanagra (1890) with his longtime model, Emma Dupont. On the wall behind the artist and his model hangs a rejected version of Pygmalion and Galatea, a more scandalous one that depicts the embrace complete with full frontal nudity. Alongside it in the artist’s cluttered workshop stand examples of his other famous works. It’s a bit dizzying, this lean towards the meta, a hall of fame of sorts within a painting about a sculpture. A painting about a myth about a sculpture whose creator’s obsession brought her to life. A myth a that’s unsettling to me, that feels a little like The Velveteen Rabbit meets The Picture of Dorian Gray. Gérôme seems to have never tired of gazing upon his own creations, of surrounding himself with them and revisiting them to make inexhaustible variations on a theme. It’s easy to see the Pygmalion in him. He even signed the painting on the base of the sculpture of Galatea, his signature taking the place of Pygmalion’s. The epitome of the male gaze, Pygmalion found himself under the obsessive eye of another male sculptor.

Looking more closely at Gérôme’s Pygmalion and Galatea, other details come into focus. This studio is not Pygmalion’s but Gèrôme’s. Selene, one of his famous bronzes, sits on a shelf next to other sculptures. One depicts a woman in profile gazing into a hand mirror. Another is of two hooded figures, a woman and a child. The woman holds one hand to her mouth, while the other hand seems about to shove the child behind her to block its view of the lovers’ embrace. A pair of theatrical masks, Tragedy and Comedy, hang on a wall. The aegis, Athena’s shield, rests nearby. The shield’s polished, mirror-like surface is adorned with Medusa’s dead-eyed-but-dangerous stare. The objects gathered in the background of Pygmalion/Gèrôme’s studio are about seeing and being seen. Mirrors and masks. I pointed out these details to a friend, my agitation rising as I struggled to articulate how the more I looked at the painting, the more it bothered me.

“Look again,” I said. “Isn’t Pygmalion’s embrace a little, well, rough? Doesn’t it look like Galatea’s fingers are trying to pry his hand off her ribcage?”

“But he’s the one reaching up to her” my friend counters. “She’s literally above him, in a position of power. He’s the supplicant here.”

“But she’s literally on a pedestal! She’s not a real woman, she’s his ideal of one!”

He cautiously suggested that I might be reading too much into the painting. I laughed and recalled an excerpt from Oscar Wilde’s preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray: “Those who find ugly meanings in beautiful things are corrupt without being charming. This is a fault.” Maybe I am reading too much into it. Or maybe I’m just so tired of being projected upon that I’ve started projecting back. I’m a typically quiet woman, which makes me cold, aloof, intimidating. When I was married and I spoke up in public, or God forbid, laugh too loudly, my husband would pinch my thigh under the table and hiss at me to “stop using my dyke voice.” I’ve been called a whore for being the victim of sexual assault. Hell, I’ve been called a whore for smiling while wearing a sundress and having a nice day. Projection is a vital ingredient of cruelty—it’s a lot harder to treat someone badly if you actually see them as a human.

While we can’t see her face, the model for Galatea was almost certainly Emma Dupont. Imagine her on the modeling stand in Gèrôme’s drafty Parisian studio, her right arm encircling empty air where Pygmalion’s shoulders would be, left hand pinning an imaginary palm to her breast, knees locked and trembling to counterbalance that lean into nothingness. I’ve held similar poses, ones in which an integral piece is missing. I’ve pretended to pour water, lift the lid of an imaginary box, reach toward an absent lover’s face. Without thinking, I’ve settled into poses identical to Dupont’s when she modeled for some of Gèrôme’s most famous sculptures: The Ball Player, Baccante with Grapes, and Corinth. The classical art training I’d received prodigiously early in life left its mark so firmly that contrapposto became muscle memory.

I’ve worked as an artist’s model for over a decade and a half. (“And your rates have never gone up!” laughed my friend who once worked full-time as a model for the huge animation studios in LA.) They haven’t gone up because it’s not exactly a bread-and-butter gig in this town, at least not anymore. This little mountain town used to be an artist’s haven, but now very few artists can afford it. I have day jobs that pay the bills. I pose because I love it. Because it is mentally and physically challenging. Because I get to meet some very interesting people.

The only figure drawing an artist ever gave me—conté crayon, side view, reclining—my husband asked to keep when I moved out and has surely since thrown away. As the gray hairs come in and my backside bears increasingly less of a resemblance to that of Galatea, I find myself wishing I’d asked to keep a sketch or two over the years. For posterity.

Over the course of the twenty years that Emma Dupont modeled for Gèrôme, she must have seen her likeliness reproduced hundreds if not thousands of times. Here she is: a Greek athlete. Here an odalisque. Here an allegorical representation of Truth climbing out of a well. Imagine her standing before an army of Emily Duponts, face to face with the closest thing to immortality any of us could ever get. She arranges them chronologically, from ages seventeen to thirty-seven, and examines the differences. Did Gérôme make her forever young, or did he allow her likenesses to mirror the inevitable changes that the muse’s body experiences? Did Emma Dupont keep any? Or was she like me, wishing she’d built a small collection for the sake of some nostalgic future self? In all her roleplaying for Gérôme’s historical subjects, did Emma Dupont ever look at a painting of herself and feel seen?

The strictly Classical artistic tradition in which I was taught stressed the ability to translate what the eye sees onto the page as accurately as possible. Still life after still life, plaster bust after plaster bust, we learned to measure out proportions with our thumbs along the length of our pencils. We studied anatomy books and skeletons, closely examining how the human body built itself out layer by layer from its calcium frame. Live models were the ultimate test: not only was the anatomy in motion, but we had to capture the motion itself. Gesture sketches were part of our low-stakes warmup sessions. On cheap newsprint I tried to capture the movement of a pose as quickly as possible, often ripping the thin paper with my pencil’s enthusiastic swoops and strokes. Contour drawings, the second part of our class warmups, were the most sensual of marks—following the topography of the figure’s surface in one continuous line with a ball point pen, folds and joints became valleys and summits. At the time, it was the closest I could get to explaining how I saw my own body as an extension of the ground I stood on. It’s the closest I can get now to describing love. The kind of love the poets seem to love best. That Pablo Neruda kind of love. The kind that delights in tracing the architecture of the beloved. The kind of love you feel when you lay your head on their chest and listen to their heartbeat as it chants wonder, wonder, wonder.

I remember nearly every model that I drew in those night classes. The first naked man I ever saw was on that modeling stand: a local sculptor who carved his poetry into cow bones with a Dremel tool. He kicked up into a one-armed handstand and held it for what felt like forever as the class scrambled to get down the topsy-turvy athleticism of the pose as quickly as possible. Except for me. Fourteen-years-old and frozen with my pencil in midair, I just didn’t know where to look, so I drew his elbow as it strained to balance his weight. All of the models seemed incredibly glamorous and bohemian to my young eyes. There was the gorgeous, head-wrapped Black woman with a rose tattooed on her thigh. The skinny white girl who had such luxurious pelts of soft fur under her arms that it looked like she had small animals nestled there. The deeply tanned mural painter who’d covered his Jeep bumper to bumper with stolen hood ornaments. The barrel-chested Zen monk. I wanted them to like the drawings I made of them so badly that, like an athlete under pressure, I choked.

The glide of pen over paper as I draft this essay feels almost as good as tracing a line along the contours of the body. It’s taken me most of my adult life to reclaim the pleasure of making a mark. Back then, as classes intensified and my skill increased, the sensuality got hammered out and replaced by stress. I wasn’t the only one who cracked under it. One night another student hit the end of his rope. He walked out after he flung a pencil across the room so hard it impaled a finished canvas hanging on the wall. We were taught that we had to get it right. And I couldn’t get it right—or at least I thought I couldn’t. I was unaware of the myriad ways in my life in which I could and would eventually fail. Looking back over my drawings from those days I can give myself some credit. They’re really pretty good. The linework especially possesses an emotional quality, a lyricism. But the rigorous training I received became warped in my mind until I honestly believed that it was better to make no mark at all than to make an incorrect one. I couldn’t stand the blank, accusing face of the empty page. So I stepped around to the other side of the easel.

There’s a couple I’ve never met who have my portrait hanging in their Brooklyn apartment. Their first date took place at a tiny Italian restaurant in Oxford, Mississippi, where my portrait hung as part of a show. Years later the bride tracked down the artist and purchased it for her husband as an anniversary gift. I’m not sure why that painting specifically caught her eye. It probably had something to do with how the artist captured the rich red of the leather chair I was sprawled in, how its ruby glow matched the wine in their glasses. It’s uncomfortable to think that it might have had something to do with the painting’s subject: the impossibly young girl with the impossibly long legs. The one with the dreamy-sad face like a Mazzy Star song, who’d eventually leave her Ivy League painter for the town’s biggest train wreck.

A few months ago, dug out an old shoebox from under the bed and found the reference photos that were taken for that painting. It’s an experience we’ve all had, going through old photos and reminiscing, but it’s a unique experience to look at a painting of yourself from the past. It’s not quite you. It’s an interpretation of you. There are three filters laid upon each other as you gaze into this mirror. Reality tilts, turns kaleidoscopic—the eyes you have now are looking through the eyes of someone you haven’t spoken to in years who is looking upon a you that, in many ways, you no longer are. How did you get your hair to be that long? Why do you look so sad? Baby Girl, you’ve only just met the blues.

Before it hung in the tiny Italian restaurant, the painting hung in a tiny hometown gallery. At the packed opening, my high school art teacher shouted at me above the din, “Good Lord, child! Is that nekkid girl you?”

“No ma’am,” I replied, pointing with the plastic cup of box wine that I was just now legally allowed to drink. “I’m over there.”

She came to the opening because we had the same high school art teacher, the painter and I, and we both adored all four feet and ten inches of her. He, of course, had been one of her darlings. She had me stay behind after class one day and asked if I wanted to talk to the school chaplain—we didn’t have a counselor—because my art seemed disturbed. This made me one of her darlings too, in a way.

In unconscious rebellion to the perfectionism of my night classes at the tiny studio downtown, I’d fallen in love with Basquiat and would spend my time in AP art class digging corrugated cardboard out of the trash behind the cafeteria to cover with oil-pastel imitations of his scrawled and angry brilliance. My early attempts at poetry marched along behind the figures, falling off one edge of the cardboard only to pop back up on the other side, a voice oblivious to any listener but desperate to be heard. There’s another projection that often happens with quiet girls: people see them and think well-mannered. Teachers write comments like “a joy to have in class.” Parents reassure themselves: She’s fine. This teacher was the only one who saw how I stood on a precipice: a motherless child who’d never see the inside of a therapist’s office until her thirties. A girl who’d fall, unseen, through a series of older men, desperately reaching for that handhold called love.

There are actually two portraits of me from the Italian restaurant art show. The one hanging in Brooklyn is nearly life-sized: I am sitting in a red leather armchair in my boyfriend-the-painter’s blue Oxford button-down, legs stretched out towards the viewer, my dirty bare feet kicked up on an ottoman. The one hidden behind my father’s bookshelf in a dusty corner of his office—the one given to me as a wedding present for my own doomed marriage that was so short-lived that the painting turned out to be more of a divorce present—is smaller. Same sad-eyed indie girl in a blue oxford button-down, same bare legs this time knees-up and folded into a blue and white striped chair.

“You look like a Jezebel” my stepmother says. Given the fact that I am fully covered, there’s nothing overt about the painting that warrants her clicked tongue. My stepmother can be a surprisingly sensitive person, however. She’s picking up on what he didn’t paint: Early-morning sunlight. Crisp white sheets on a narrow bed. The smells of sleep and sex and laundry detergent. What it meant, exactly, for me to be wearing the shirt of this much older man.

We’ve all felt it, the biological phenomenon known as “gaze detection,” that creepy sensation of feeling someone staring at you, of feeling every downy hair on the nape of your neck rise in alarm, the area we refer to in dogs as hackles. Now imagine standing naked on a platform in a studio—it’s always chilly, the studio, wherever it may be—feeling several pairs of eyes staring at you, causing goosebumps to rise wherever on your body a gaze lands. You discover that your entire body has hackles. You get used to it.

It works both ways, this vulnerability. While I might steal a glance out of the corner of my eye after I step down from the platform and wrap a bathrobe around me, and I might cast a passing glance over the easels on my way to the bathroom, I don’t linger. I know better. Some artists turn their sketches over, cover them with a blank sheet of paper during the breaks. My friend who worked in the big animation studios is nothing if not charismatic. Like Emma Dupont, she often posed as characters: a Viking shieldmaiden, a psychedelic Alice, Marie Antoinette. A loud Italian with undeniable main-character energy, she did all her own makeup and costuming. She chatted with artists on her breaks, and her favorite sketches ended up on her social media feeds. My friend’s future self, her potential children, maybe even grandchildren, will have plenty of proof of her glory days. I can only assume that they do things differently out in Hollywood, a place where everyone seems desperate to make their mark, to live forever in one form or another.

In Gèrôme’s painting The End of the Pose, Emma Dupont throws a cloth over a sculpture of herself to protect it from dust while she herself remains nude, her glorious backside bare to the viewer while Gèrôme cleans his tools. The statue’s face is already covered, as is the face of the tiny child tucked behind her. The statue is a clay maquette of Gèrôme’s famous marble Omphale, the Lydian queen who enslaved and later married Hercules. What does it mean, to protect a representation of oneself while remaining exposed? The fact that Dupont is covering the artwork while Gérôme cleans up points to a collaborative relationship between the artist and his muse. On the stand lies a tiny vermillion flower, an offering, like the showers of roses tossed by adoring audience members at the end of a spectacular performance. There is a sweetness to the scene, a simple intimacy between the artist and the model that makes me think that maybe Pygmalion and Galatea did live happily ever after, after all.

The first time I modeled for a group of sculptors, I thought this must be what it feels like to be a planet. The modeling stand stood in the middle of the studio, rather than against one wall. The walls were white, the stand was white and I though the floor was white too until I realized it was covered with a thin layer of fine white porcelain dust. The casters of their sculpting stands left tracks in it as the sculptors orbited me like dervishes. I was used to the sensation of eyes upon me, but I was completely unused to feeling those eyes move around me, of having them move through my line of sight like constellations across the night sky and then disappear as if under a horizon. I was grateful to be sitting down, my bare butt firmly planted on the sheet-covered stool, because I felt like I might float off into space. At the end of the session the floor itself was art: the tracks made by the paths of the sculptors working in the round had blurred together into a single circle: the ensō of Zen calligraphy, created in one meditative brushstroke—representing everything and nothing.

Posing is a form of meditation. I find a focal point somewhere in the middle distance: a light switch, a dent in the wall, an object on a shelf that I know won’t be moved. As I relax, I can feel my field of vision grow astonishingly wide. As I grow uncomfortable, an inevitability no matter how comfy the pose seems at first, my field of vision shrinks back to that focal point. If the pose becomes excruciating, as they often do, nothing but that focal point exists—a vignette in a silent film slowly fading to black—and I count to ten over and over until the timer goes off. Then I rub feeling back into limbs, sip some water, and stretch as much I can in the five-minute break before heading back to the stand for another twenty minutes of complete immobility. Repeat for three hours, sometimes four.

I pride myself on rarely breaking a pose, on creating interesting shapes with my body that won’t leave me with nerve damage although I typically lose circulation in some body part or another. I may not be the most agile or athletic figure model you could hire, but I can stay very, very still.

What did Emma Dupont think about as she fixed her gaze on some dent in Gérôme’s studio wall? Was she thinking about how the pins and needles in her right foot had long subsided into numbness? Was she wondering what happened to the boy she accompanied to Paris so many years before, the one she thought was her destiny but who abandoned her once they reached the big city? Did she take the pain she felt in her strained back, her numb toes, her grumbling stomach and send it all out in a wordless curse upon him, wherever the hell he may be?

It’s a lot harder to pose for a portrait than for a figure drawing. While sitting for a portrait, you have to remain aware of what your face is doing, of how emotions will inevitably pass over it like clouds over a summer field. Skilled portrait artists can capture a moment’s expression, arrest a fleeting emotion rather than create a composite of the model’s face over the course of several hours. It helps them achieve this if you can empty your mind.

Artists invariably comment on my stillness and ask me how I do it. If I feel like they can take my dark sense of humor, I tell them the truth—that I’ve been forced to dissociate in order to survive so much of my life that I’ve honed it into a superpower. I feel a kinship with Fernande Olivier, who fled an abusive marriage in 1900, renamed herself, and started modeling for Picasso. In her memoir—which she used to extort enough money out of Picasso to support herself after he dumped her for another model—she describes her own experience of dissociation while posing:

To pose well you have to forget you’re posing…forget life, forget who you are, lose yourself in another life completely within yourself, a life that’s filled with a happiness you could never find except in our dreams. Luckily I have this facility for dividing myself in two, which is ideal for this exhausting job.

Picasso painted over sixty portraits of Olivier, but my favorite is Fernande with a Black Mantilla. In Picasso’s painting, the same sad poet eyes of the girl in the red leather armchair gaze at you out of a French face. The fog of the gray background drips and splatters onto her shoulders like bird droppings. She looks like a woman who has been through things that taught her how to divide herself in two.

Gazing at Olivier’s tired-beyond-caring expression I remember weeping in front of Käthe Kollwitz’s 1904 self-portrait, one of the fifty or so she made in her lifetime, in which she looks so exhausted by all the horrors she’s seen that I wanted to hold her. The Kollwitz Museum in Köln is tucked into the top floor of an office building, and I had a hell of a time finding it. I was determined, however, to make a pilgrimage to see one of the artists I admired so much when I was young. She inspired me to draw self-portraits. I tried to make them as honest as possible, like hers, which was probably another thing prompted my teacher’s concern. Wiping my eyes, I found a poster of the drawing and carried it in my arms all the way back home, where I tacked it up on the wall. My husband hated it.

“I just don’t get why you would want to look at something so depressing every day. Didn’t you say it made you cry?”

What I couldn’t explain to him, the man who left bruises on my arms and holes in our walls, was that that through all the horror that went on behind those closed doors, Käthe Kollwitz was my only witness. That her gaze held mine and said I see you.

Jean-Léon Gérôme was not the only French sculptor who saw himself in Pygmalion. Auguste Rodin, a veritable titan of sculpture, carved his name next to the mythical sculptor’s on his rendition of Pygmalion and Galatea. This Pygmalion is an undeniable self-portrait. Bearded and past his prime, his face is nearly buried in Galatea’s belly. Her gaze is averted, and she leans away, her legs locked in rough marble up to the knee as she leans on an a very phallic protuberance of stone. In Rodin’s sculpture it is impossible to tell in what state of metamorphosis she is: statue or woman. Is she trapped somewhere in between? Is this Pygmalion-Rodin an assailant or a madman trying to seduce a chunk of marble? Does it matter? What matters is this: he looks like Hemingway by way of Jerry Garcia, which is to say he looks like my father. He looks like that one painter whose phone calls I never answer after five in the evening because I know he’ll be drunk and because if he ever got creepy with me it would break my heart.

I count myself incredibly lucky that I’ve never had any inappropriate encounters during my art modeling career. Even that one painter—a real Old World-style master with a dirty old man reputation—has been nothing but respectful to me. “You’re the only model I’ve ever seen him not paint bigger breasts on,” one of his colleagues commented. The tiny oil he produced from the hundred hours I spent in one pose still hangs on his wall with an astronomical price tag under it. By the time I finally found the courage to leave my marriage, terror had whittled my body down to ninety pounds and modeling was the only place I knew peace. His studio was my sanctuary.

I felt like the luckiest person alive every morning I climbed the stairs to his studio and stepped back in time: Shelves of old books, plaster busts. Brushes and jars of hand-ground pigments. The smell of rabbit-hide glue drying on foolscap, linseed oil and turpentine, fresh coffee and brindled dog. Morning light from the high windows bathed it all in rosy gold, and every twenty minutes I would get up and stretch before padding around in his bathrobe, sipping coffee and trying hard to burn it all into my memory forever.

This is also why I do it: to stop time. To suspend a moment like a pearl on a string. Or like that one perfect cabochon opal once tipped into my palm as payment.

In 2011, a previously unknown painting of Emma Dupont came up for auction in Paris. The pose, used as a reference for Gèrôme’s Pool in a Harem, looks like it would’ve been hell to hold for long. Dupont is lying propped on her elbows and left hip, twisted around to face the viewer so that her buttocks and breasts are on full display. She gazes out directly at you with a knowing little smile. This isn’t the expression of a model white-knuckling her way through pain by dissociating. She’s flirting with you. It’s a shockingly contemporary piece depicting a woman in full possession of herself, and here’s the best part: the painting belonged to her. Emma Dupont’s descendants put it up for auction that December, and while I could never imagine parting with such a treasure, I can imagine it hanging in Emma’s little Parisian apartment. I can see a silver-haired Emma pausing to stand before it as she sips her morning café au lait, smiling at her younger self from across the span of a life well-lived.

Works Referenced

Olivier, Fernande. Loving Picasso: The Private Journal of Fernande Olivier. New York: Abrams, 2001.

Waller, Susan. “Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Nude: Emma Dupont: The Pose as Praxis”. Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide: A Journal of Nineteenth-Century Visual Culture, vol. 13, issue 1, 2014. http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring14/new-discoveries-jean-leon-gerome-s-nude-emma-dupont . Accessed 18 March 2023.