When I open the door of my father’s truck, all…

In Conversation: Neema Avashia

“In truth, I’ve always felt uneasy in my relationship to the word ‘Appalachian’… do you not count if you are Brown, Indian, the child of immigrants who moved to a place out of necessity again thirty years later, when work disappeared?” Neema Avashia writes in Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place, her debut essay collection.

Published in March by West Virginia University Press, the book explores the economic decline in her West Virginia hometown, the struggles to represent her intersecting identities, and the significant relationships that shaped her as a child in Appalachia. Avashia’s work has been published Bitter Southerner, The Kenyon Review Online, Still: The Journal, and other magazines. Avashia spoke with writer and Appalachian Review student assistant Skylar Bensheimer to discuss her new essay collection.

■■■

SKYLAR BENSHEIMER: I wanted to start with the opening essay, “Directions to a Vanishing Place.” It feels like a natural way to start the collection, especially with the second person and the directives. Did you know you wanted to begin the collection with that essay?

NEEMA AVASHIA: Yes, largely because it was the first essay I wrote in the collection. It was the first essay to be published, the first essay that set the direction for what I was going to do. For readers who are unfamiliar, I felt like I needed to ground them in the place, and I felt like there wasn’t another way to do that besides taking them there. If I start with this idea of directions and I locate you in the place, then with everything that comes after, there’s less burden to establish place. It still has to happen to some extent, but it’s less of a need in other essays if I do a good job in that first essay.

SB: In the opening pages, you listed when and where each essay had been published before, and they were all published in the last couple of years. It’s also a relatively short book, but you still cover a lot of subjects and touch on a lot of topics. What was the process like when you were compiling these essays? Were there cuts that you had to make?

NA: It was actually the opposite. It wasn’t so much cutting as it was figuring out if there was enough there for a collection. I have a mentor, Geeta Kothari, who’s a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, and she said, “You need 50,000 words. You can’t do anything with this until you have at least 50,000 words.” So, there were some ways where I thought, Okay. I’m going to see if I have enough things to say that can get me to 50,000 words and that can feel like a complete collection. It wasn’t so much cutting as it was writing to a goal or writing to a place where I felt like I had a complete collection.

SB: One of the through-lines that really interested in the book was this theme of isolation, whether that is being a minority in a conservative, mostly white area, the move from rural West Virginia to Boston, where you describe neighbors not really knowing each other, or when you write about the pandemic. Would you characterize those experiences as isolating, or do you think of them in a different way?

NA: I think “isolating” is the right word for them. It’s taken me a long time to understand, but when you’re somebody whose identity is so intersectional, it can be really hard to find places where you don’t feel isolated because even if one or two parts of you are represented, the thing that starts to surface for you is the thing that’s not represented. That becomes the thing I’m most aware of. There are not a lot of places where queerness, Appalachian-ness, and Indian-ness are held together, and because of that you can end up in disconnects where people can see parts of you, and they can understand parts of you, but they don’t necessarily understand all of you. I talk about that a lot in the book. My family very much understands the Appalachian and Indian parts of me, but the queer part is a thing that they’re still trying to figure out. You can even trick yourself into feeling like you’re really close, but then something will happen that will remind you that you’re not as close as you thought you were because there’s a disconnect again. Isolation is a thing that I feel like I’ve experienced a lot in both trying to establish strong connections with people but also seeing where those connections fray or can become tenuous because the visibility of all parts of my identity isn’t held in a space.

SB: You mentioned establishing relationships, and it seems like that’s how you characterize your connections to Appalachian places and cultures—through the relationships that you have with people rather than through land and geography. Is that how you’d also define your place in Boston, or is there a different emphasis on geography there?

NA: Living in Boston, I actually feel more connected to Appalachian geography. The day before yesterday I was in West Virginia, and I am so aware that I live on the coast now, and so aware of how I think coastal geography makes people different. When you’re in the mountains, you know you’re really small. You’re reminded of how small you are all the time, and when you live on the coast, you don’t always have that humility because you don’t have the mountains around you saying, “You’re not as big as you think you are.” In a way, my appreciation and awareness of how Appalachian geography shaped me was heightened once I left and once I became aware of what it’s like to live in a place where there are no mountains. How much less grounded do I feel because I don’t have those mountains around me? The through-line in every place where I’ve lived that I think is a significant result of growing up in Appalachia is the relationships. I learned how to build relationships from people in Appalachia, and that is something that I have carried throughout my whole life, that way of knowing people and seeing people, connecting with people, supporting people. Everything I know about how to be a good human and take care of other people, I learned at home, I learned growing up. That is the driver even in my Boston life. People think I’m very strange because that’s not how other people in Boston behave, but the way I build relationships is probably the most Appalachian part of me.

SB: Returning to the theme of isolation, you also talk about social media in the essays. Especially in the last couple of years, it can both serve as a connection between people, but it’s also a way for people to blindly spew hatred without having to reckon with those actions. With Mr. B you describe this as a “lost ability” to see each other. Has your relationship with social media changed at all? Is there a healthy way to navigate it currently?

NA: There could be. I think part of what happened during the most intense period of this pandemic, when things were locked down, is that people were being reduced to their social media presence, which was already happening before but got even worse. Before that, someone could be spewing ridiculousness on social media, but you would see them. And those moments when you saw each other in person, and you had three-dimensional bodies and feelings and experiences, could mitigate whatever intensity was happening online.

Then we went into this time when we were actually physically isolated and socially isolated from each other and didn’t have those in-person interactions to do the mitigating anymore. Everybody gets flattened. Everybody gets reduced. There are so many things said online—and I would put entire paychecks on this—that no one would say out loud. Most people I know believe themselves to be decent people and would not utter the phrases out loud to someone that they will post online about that person’s identity. But you weren’t seeing those people, and you weren’t getting that check telling you that this isn’t a decent way to behave. That exacerbated what had already started. It’s not new. 2015 and 2016 was when we saw this intensify. It could be healthy if we could hold it in the balance of physically connecting with people and then having social media connections with those people, but when it’s all online, I don’t know that it can be good.

That said, I’m on book tour right now, and one of the neat things about it is I’m meeting people who I only knew online prior to this, people who I connected with on Twitter because they’re Appalachian folks, because Appalachian Twitter is the best Twitter. They’re people I connected with because we shared interests and we shared ideas, and now I got to see them in person. That was really lovely. Being able to put a three-dimensional being behind a face or handle or ideas has been powerful for me. If we were not thinking about social media as a substitute for meaningful interaction but as a support for meaningful interaction, meaningful in-person interaction, it could be ok, but we ended up in a situation where social media is the only interaction, and I don’t think that’s a good space.

SB: I completely agree. I’m a big basketball fan and enjoyed reading your essay, “Be Like Wilt.” You later write about reading that essay at the Hindman Settlement School and being unsure if that would resonate with people. That reading turns out well, but has that been a rare connection for you elsewhere—the literary world and the basketball world? They can seem disparate at times.

NA: It’s not weird in Appalachia. One of the coolest things about reading that essay at Hindman was how many people didn’t “know” Carl Bradford but knew Carl Bradford. They had a Carl Bradford. Especially in rural places, sports are a formative part of a lot of peoples’ identities, and it isn’t until you get older that you feel like these are polar lines where you’re either a sports person or you’re an arts person. Growing up I didn’t feel like that was a binary or that I had to choose. When I’ve shared that essay with people who aren’t sports people, the thing they’re able to resonate with is the idea of mentorship and the idea that people who aren’t your blood family can play such a formative role in developing who you are as a person. That’s been a hook for people who, if they aren’t basketball people, can find a way into it. I actually pick that essay a lot for readings because I think it’s a good one to bring people into the space. Even if you’re not a sports person, the image of this scrawny kid who can’t make a basket is an underdog story you can root for. I rely on those elements of it—the relationship, the underdog story—to hold onto people for whom basketball isn’t as interesting of a concept.

SB: You write about an “Indo-lachian” identity, but you also describe a potential exodus of Indian families from West Virginia after your parents’ generation. If Indo-lachians are, as you describe, a “demographic anomaly” in West Virginia, how do you hope that your story and your history resonate with other communities?

NA: This points to the title of the book, but so often in mainstream narratives about Appalachia that don’t come from [the region], Appalachia is reduced to white, Christian, straight, and homogenous. When I wrote this [book], it wasn’t necessarily that I thought that I was only going to represent this Indian-American experience. Part of what I was hoping to do was to point out that Appalachia is a much more complicated place. There are immigrant communities that have been there for a long time. There’s a Black community that has been there since before West Virginia was a state. There’s a diversity and a complexity to Appalachia that it isn’t afforded a lot of the time. The book that became a bestseller and was on the bestseller list for fifty-one weeks doesn’t complicate that narrative about Appalachia at all. There are tons of other writers who do. There are queer Appalachian writers, Black Appalachian writers, and Indigenous Appalachian writers who are putting out amazing books but they’re not the ones who are getting plastered on the front page of the New York Times.

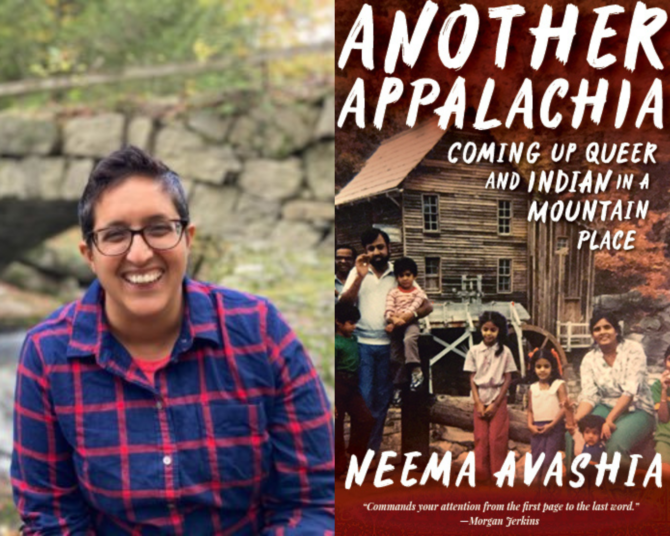

I think a lot of people outside of Appalachia are invested in perpetuating these stereotypes and this flattened understanding of Appalachia. My hope by writing this book was to make people pause on that stereotyping. Right from the outset, when they look at the cover, I want their understandings to be upended. In the image you can see:

It’s clearly a rural place. It’s clearly in the fall. It’s clearly in Appalachia, but the people standing in front of Babcock mill are the members of my extended Indian family. I want this book to plant enough seeds to make you think, well, if there are Indian people there, there are probably other people there, too. I can’t just have this flat view of this place anymore. ■