With all of the bombing and explosions and smoke everywhere,…

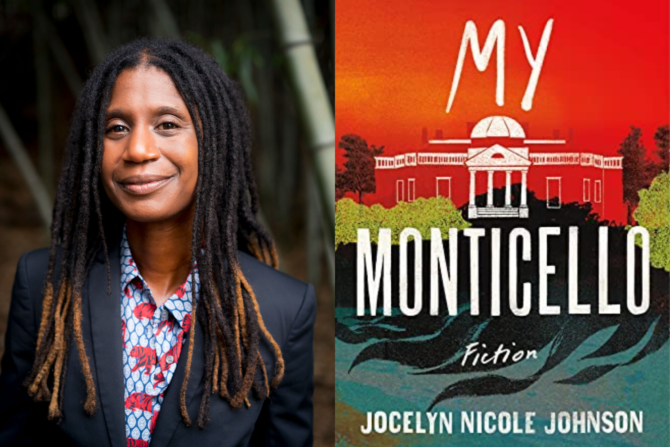

In Conversation: Jocelyn Nicole Johnson & Monic Ductan

Timely: that’s but one word to describe Jocelyn Nicole Johnson’s electric debut My Monticello, a collection of stories and a novella that bears witness to the white supremacy of both the past and present. Set in and around Charlottesville, Virginia, where Johnson lives and writes, the book centers on Black and Brown characters as they navigate the notion of home, both as a physical and spiritual place: the single mother who dreams of buying her first home, the mixed-race woman who changes her name to escape oppression, and in the title novella, a diverse group of neighbors—led by a descendant of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings—who turn to Monticello in the face of racist violence.

Critically acclaimed upon its release last autumn, My Monticello recently received the 2021 Weatherford Award in Fiction, given to the work of fiction that “best illuminate[s] the challenges, personalities, and unique qualities of the Appalachian South.” Johnson spoke with essayist, fiction writer, and Appalachian Review contributor Monic Ductan about My Monticello and its upcoming adaptation for Netflix. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

■■■

MONIC DUCTAN: Of the stories in My Monticello, which is closest to your heart?

JOCELYN NICOLE JOHNSON: I included these stories in the collection because they are all close to my heart and related to one another in their shared exploration of home, longing, dislocation, and loss. The story that is probably closest to my way of being (though not my lived experience) is “Buying A House Ahead of The Apocalypse,” a slim investigation of existential dread woven through with pop culture references, Black girl hair considerations, and aspirational shopping, all in the form of a bulleted to-do list.

MD: The first story in your collection, “Control Negro” feels very timely in regards to the protests against police violence toward Black men in particular. Were you inspired to write that story by learning about any recent events? Elijah McClain? George Floyd?

JNJ: “Control Negro” was inspired by a local incident that predates the murders of Elijah McClain and George Floyd. In 2015, here in Charlottesville, a Black University of Virginia honor student, Martese Johnson, was bloodied by uniformed Alcohol Beverage control officers along the crowded strip of restaurants and bars adjacent to his campus. The incident, caught on video, and the resulting heartache echoed a long tradition of excessive force wielded by institutions toward Black and brown and poor people. In my dark story “Control Negro,” I looked at one father’s twisted attempts to escape this intergenerational trauma.

MD: Your book is a novella and a collection of stories. Can you say a bit about why you arranged it that way? Did you set out to write a book of stories or did it just kind of happen organically?

JNJ: I was writing what I thought were stand-alone stories when I began to recognize a pattern. Most of my stories were set in Virginia and explored some aspect of belonging. Seeing this, I started to imagine a set of stories like pins pressed into a map of my home state. I wrote the novella “My Monticello” last, but because it pulled at so many of the threads of the earlier stories and even echoed a few of their phrases, I felt it belonged with them.

MD: Can you say a bit about your inspiration for writing the book? Who or what inspires you?

JNJ: These stories, by and large, were inspired by my view of the world between 2015 and 2019—moments of trouble, longing, and hope—everything from seeing children seek power in a classroom to watching a deadly white nationalist rally wreak havoc on my town of Charlottesville in August of 2017. I often write when I am bewildered by the world, to avenge something, or try to figure something out.

MD: I read recently that your novella, “My Monticello,”is being made into a Netflix movie. Can you tell us more about that? Do you have details about when it comes out or about the narrative approach to telling your story on film?

JNJ: Yes, the novella “My Monticello” is currently being adapted into a film for Netflix and is in the screenwriting phase! The challenge of these kinds of adaptations is to make the internal external and visible. My small contribution as one of the executive producers is to advocate for the big ideas of the story: In this case, a celebration of feminine and communal power in the face of racial and environmental reckoning.

MD: What do you see as the most helpful piece of writing advice you’ve received?

JNJ: I often think back to when Aimee Bender, who was leading a workshop at Tin House that year, drew a line on the whiteboard to illustrate how much we should shift our stories in reaction to comments from our classmates. On one end of the segment, she wrote something like, “Change Everything” and on the other, “Change Nothing.” Then she placed a dot toward the middle but slightly closer to Change Nothing. She talked about how, when getting feedback, a writer should be open to critique and suggestion, but not too open. What I came away with was an affirmation that, as artists, we had to value or own instincts and intentions.

MD: Do you have any rules for writing?

JNJ: Try to enjoy it. Try to keep at it.

MD: Could you recommend some writers you enjoy? Writers from which you’ve learned the most?

JNJ: I’m drawn to writers who draw from different genres to get at truth, writers like Octavia Butler, Charles Yu, and Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah. I’m also a fan of nuanced moments made up of sharp sentences, as seen in writers like Toni Morrison, Richard Wright, Jhumpa Lahiri, Junot Diaz, Ruth Oseki, Garth Greenwell. I love the short story form, and have been moved by collections from writers like Danielle Evans, Jamal Brinkley, Cal Angus, Te-Ping Chen, Dantiel Moniz, and many others.

MD: You’re a Virginia native and a person of color. Do you ever write from your own personal experiences with racism or white nationalism?

JNJ: As I mentioned earlier, I absolutely write in response to what is happening in my community and in my country, including my experience of race, racism, and white nationalism. In this collection, I’ve written in response to conversations overhead, a travesty caught on video, and a public spectacle of hate. Even when I’m imagining, I’m writing from what I’ve seen and heard and felt.

MD: There’s been a lot of talk recently about people of color and the publishing industry. Do you have any advice for other writers of color in terms of breaking into the industry or finding a wider audience?

JNJ: Read widely. Be open, but cultivate your own sense of intention. Learn to love your own words, and if not your words, then at least the process of putting them down and honing them. Remember, you cannot control the world, but you can choose your words, and the ordering and reordering of them. Meanwhile, find community (a trusted group of writers, a mentor or two). When you’re ready to send your work into the world, look for partners that believe in your work and your intentions— journals, agents, editors, a team. Try to appreciate it when any reader connects with your words, and don’t pin your joy on some external goal of a certain kind of publication. Publication has its own anxieties, even under the best of circumstances. For me it took many years and three agents before I published my first book at age fifty. No one can wait that long for joy. Find joy in your words, in the process of making and trying.

MD: Congratulations on winning the Weatherford Award for Appalachian fiction. I know writers are always labeling themselves and being labeled by their readers. Do you see yourself as an Appalachian author? A Southern writer? If you were to apply labels to yourself or your writing, what would they be?

JNJ: Thank you! I’m honored to be recognized by the Weatherford Award and described as an Appalachian writer. I could also be called a Southern writer, a Black writer, an American writer, a writer of literary and low-key speculative fiction. By and large, I appreciate being encircled by multiple descriptive labels that invite readers in, hopefully with each label complicating and enriching the next.

MD: I watched your GMA [Good Morning America] interview with Robin Roberts and she asked about the rally in Charlottesville and at one point you said you were inspired by those events to write My Monticello. Could you describe your hometown? What do you love about it? What do you dislike? How has your home place influenced your writing?

JNJ: My experience of my home state isn’t necessarily about what I like or dislike. Virginia has been the ground beneath my feet, where many of my loved ones live, where my son was born. Virginia is where promises have been made and broken. An early engine for this collection was thinking about the ways Virginia, and America, feel both like home and not like home, to me. I wanted to explore and share my longing for an incontrovertible home for my nerdy, artsy, Black girl body, and the insights that come from straddling that border. ■