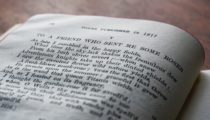

You remember in Rome you stood in front of a…

Where Have All the Safety Pins Gone?

2016 was the year of trauma. Prince died. Muhammad Ali died. Harper Lee died. The Pulse nightclub shooting occurred. Philando Castile was murdered by the police in front of his girlfriend and her four year old daughter. Donald Trump was elected president. Trauma. One trauma after another.

My life has seen its fair share of trauma. I was given up for adoption when I was just a few days old. I was suddenly taken away from the foster family that had taken care of me from the time I was surrendered until I was two years old. I was adopted by two parents, but only one of them loved me—my daddy. I was sexually assaulted by an uncle when I was eleven. I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder at twenty-six. I was in a loveless marriage for eleven years. Trauma. One trauma after another.

But the beauty of my life is that I have always found ways to cope with my trauma. Sometimes the coping was in the form of a book like Maya Angelou’s I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings or Alex Haley’s Roots. Sometimes the coping was in the form of the stories I wrote as a little girl where I reimagined the parts of my life that brought me pain. When my adopted mother would beat me with a broom handle or a strap, I would pretend that my real mother would come flying in with a fury, slay my adopted dragon, and take me to live in a beautiful castle where little, kinky-haired girls with dark skin would be loved and cherished. Sometimes the coping was in the form of loving mother figures like my Big Mama or my Aunt Lenoria who would pull me close, hug me, and remind me that I was loved, even when I didn’t feel that way. Throughout my life, there has always been a talisman that I could reach for that brought me comfort—that told me, this too shall pass.

So, after the trauma of the election of 2016, something happened. At first glance, it seemed pretty innocuous. A national “movement” occurred that involved safety pins. Black people, people of color, and marginalized people in general were supposed to see those safety pins on the wearer and interpret the meaning of them to be the following: This person is an ally. We are safe with them. They will stand up for us in the midst of a racist occurrence. They will advocate for us when we are not in a position to advocate for ourselves.

I tried to imagine myself taking advantage of this offer of allyship. I tried to imagine a situation when having a white person with one of those pins on their clothing would make me feel safe and supported. Maybe I would be sitting in a public space—maybe a park or an outdoor café—and maybe someone, a white woman or a white man, would demand that I tell them why I was there, and before I could respond, maybe they would reach for their phone to call the police on me for disturbing the peace with my Blackness. But maybe, before they could carry out the call, someone, maybe a another white woman or white man, with a huge, silver, safety pin on their shirt, would walk over and stand between me and the other white person sans the pin, and say, “Not today. Today you will not do this. This woman has done no harm. Go away with your hate.” Maybe that would happen. Maybe.

Maybe that pin would operate in the same manner as quilts hanging on a clothes line during slavery, alerting runaway slaves that they indeed had arrived at a house where they could ask, “Friend of Friend?” and feel safe. Just like that safe house during slavery meant the slave could take a breath and know they were protected, maybe that safety pin would do the same for modern day Black folks who didn’t always know if someone truly was a “Friend of a Friend.” Maybe.

Maybe that pin would become like a symbol of hope that would help to cancel out the vote that took place in 2016, electing a man who openly bragged about grabbing women by their privates. Maybe that pin could undo the damage of “good white folks” voting for someone who bragged that he could “shoot somebody on Fifth Avenue and still not lose any votes.” Maybe that pin would change the paradigm and for the first time we would turn a corner and there would be a bright, shiny symbol to alert us all that change really had come. Maybe.

Back in 2016, I posted on social media that I didn’t think the “safety pin movement” made any sense whatsoever. And it didn’t. To me. I couldn’t wrap my brain around it. I thought back to the slavery times when Harriet Tubman would sneak onto various plantations and silently take runaways on the Underground Railroad to freedom. The white allies back then were invisible. They had to be for the allyship to work. They provided their aid under cloak and dagger. They created secret safe spaces within their homes. They didn’t announce to the world they were an ally. They just did the work.

Wearing a safety pin and then announcing its meaning to the world seemed counterproductive to me. My thoughts were, if everyone knows about this safety pin, couldn’t anyone wear it and mislead someone into believing they were an ally when they weren’t? I asked that question on social media. I was shushed. I responded that the gesture felt more performative than anything else. And then I said I would not feel “safe” assuming just because a person wore a safety pin that they were an ally. Instead of being heard, I was dragged by some “allies” who challenged me on every single point I made. Called me ungrateful. Called me shortsighted. Called me everything but a child of God.

One ally unfriended me on Facebook because dammit, she was trying. And she wished Black people wouldn’t make it so hard for white allies to help them. I struggled with my emotions. I struggled to not say too much, fearing I would cause those folks who were on our side to walk away. But it was hard. I had just been told, “If you see me wearing a safety pin, I am someone you can trust.” But how could I believe that promise when my words alone were enough for them to attack me? How can you be my ally but not be interested in hearing my thoughts? How can you say, in one breath, look for me and this pin and you can feel safe, and in another breath you say to me, You ungrateful _____.

Let me give you the quick rundown on what it means to be an ally for anyone, not just Black folks.

Listen. Period.

Stop trying to run things. I get it—you are used to running things, but if you really want to be an ally, stop thinking you can both be the problem and the solution at the same time.

Stand down.

Trust that Black folks or any group of people who are getting symbolic and literal knees to the neck actually know what they need from allies.

Trust that people who have for generations been pushed outside of the margin understand fully what it will take for them to feel included and seen.

If that is too much for you, it’s okay. Maybe your allyship needs to be you cut a check to organizations doing the work. Maybe your support involves you sharing a post on social media. Maybe your solidarity means you talk to your MeMaw and PawPaw about the racist commentary coming out of their mouths during Thanksgiving dinner. Maybe your help involves you registering voters and campaigning for candidates who will serve and protect the most vulnerable members of our society. Maybe your backing is you don’t take part in the subjugation of other folks. But what your allyship shouldn’t be is you telling people what you think they need and arguing with them when they say it isn’t. Just know that some of the best allies do their work from behind, not in front.

I have always felt outside of the margin. When I was a little girl, I used to write stories and most times I would only write on the other side of the margin, leaving the space in the middle blank. I remember once daddy asked, “Why are you using so little space? You can write in the middle of the page if you want to.”

I said to him, “My words are not good enough to be in the middle of the page yet.”

Even as a small child, I didn’t believe my words were for such a distinctive place of honor. I understood, even then, that the middle of the page meant belonging and worthiness. And as a Black woman in America, I often feel like I have to continue to prove that I deserve to be inside the margin instead of trying to squeeze myself onto the edges of the page. That little girl who saw her words as being unworthy still lives inside this Black woman, and it doesn’t take a lot for her to be reminded of that young girl’s feelings of unworthiness. To this day, every story and poem I write begins on the outside of the margin.

I wanted the safety pins to be “a thing.” I wanted them to have transformative powers. I wanted to know that I could have a visual that would alert me instantaneously that yes, this person is a friend. This person will go into battle with you. But, sadly, as most performative responses to something as complex as racism and hatred of others go, so went the “safety pin movement.” It fizzled out without even a sputter, leaving us, the vulnerable, right back where we started, wondering where have all the safety pins gone?

Fast forward to 2020, and after yet another Black man died at the hands of the police on the streets with a knee to his neck and a young Black woman died after being awakened by armed, plainclothes police, shooting twenty rounds of bullets into her home, I saw something I never saw before in my lifetime. I saw people awaken. I saw allies become true allies. I saw white women and men say, “I will stand between you and the bullet.” I saw white women and men question police officers asking, “Why are you detaining this person?” I saw white women and men enter the streets of their community demanding justice or no peace.

Yes, I still saw the ugly. I still saw white women and men weaponizing or attempting to weaponize the police in situations where Black people and people of color were doing nothing more than being. I still saw systemic racism in workplaces throughout this country. I still saw poor people get the short end of the stick. I still saw the hatred. I still felt vulnerable. But I also saw hope.

Thank you for opening your heart and mind, yet again. I read your words years ago, and listened to them. I heard you. And I learned from you then, as I do again today. That is the rarest treasure, and I appreciate so much that you’ve shared it.

I now stand before the bullets. I now am that unadorned ally.