after “The White Horse” by Yasunari Kawabata In the low light…

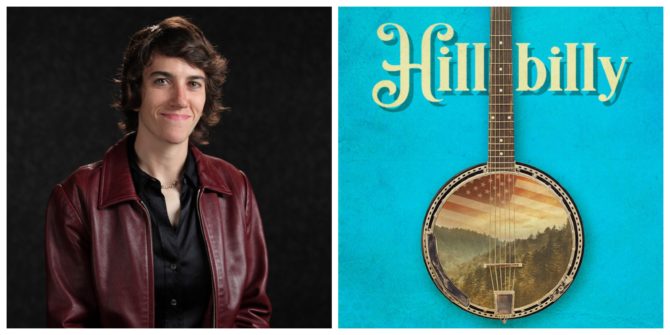

Interview: Filmmaker Sally Rubin

hillbilly, the new documentary film directed by Sally Rubin and Ashley York, is an examination of images and stereotypes about Appalachia and its people. The film works to combat stereotypes of Appalachia as a homogeneous region, using the 2016 presidential election as a window for examining how the region is portrayed in the national media. In the film, Rubin and York work to contextualize 52 and humanize Appalachians, showing images that contrast with the often abused depictions of whiteness and poverty that have pervaded the national consciousness about the region. Rubin and York hope to challenge such prevailing, narrow views of Appalachia and the people who live here, prodding those with a limited understanding of the region and its history to pause and think before making jabs about class and otherness.

The film debuted on the film festival circuit over the summer, winning the Documentary Award from the LA Film Festival and the Special Award for Documentary Filmmaking from the Traverse City Film Festival, and being mentioned as a “significant Oscar contender” in the Best Documentary Feature category.

But in an honor that perhaps even surpassed these accolades, hillbilly received the endorsement of Appalachian icon Dolly Parton. “I’m happy to see somebody trying to cover us as we really are and not what some people think we are,” she said. “It’s wonderful, the attention (the movie) paid to so many areas that are so important to all of us. I’m proud to have been mentioned in the film a time or two.”

hillbilly is now showing in select cities nationwide. Following a recent screening of the film at Berea College in September 2018, co-director Sally Rubin spoke to Appalachian Heritage about some of the trials and successes she and York had in making the film, developing an on-screen balance during the polarization of the 2016 presidential election, and providing a diverse perspective of an often simplified and stereotyped region.

■ ■ ■

EMILY MASTERS: What was the most challenging part of the documentary process when you were making hillbilly?

SALLY RUBIN: We had a couple of major challenges with the production of hillbilly. I think in some ways the breadth of the ideas in the film is certainly a strength; the film ranges wide in its coverage of psychological and sociological humanities themes that are complex and highly compelling, such as notions of regionalism, othering, code switching, co-option, stereotyping, and more. Simultaneously, the film deals with the 2016 presidential election and [includes] scenes with co-director Ashley York and her family. But this broad, sweeping look at the history of various cultural elements of the Appalachian region, including the region’s reliance on coal, as well as the survey of media representations of the region over the last century-and-a-half, combined with all of the content described above, sometimes felt like more than we could really chew while producing the movie. We tried to do so much with this film. I hope we succeeded—I think we did— but it made production overwhelming and difficult at times, and long. It took four-a-half years to make this movie. And there were times when even I, as the film’s co-director, had a hard time describing what this film was about.

Another major challenge with the production of hillbilly was working all of the threads described above into one cohesive movie. The film evolved substantially over time, as American society, politics, and culture evolved, and we had to work hard to keep up. When we began researching this film back in the fall of 2013 we were primarily aiming to make a film about the history and evolution of the “hillbilly” stereotype over the past century and a half. But as we got into making that movie, it became clear that if we were going to tell a story about what Appalachia isn’t, we also had to include 55 what Appalachia is. At that point we began to work in the alternate Appalachian identities that we so rarely see in the media— self-described “Fabulachians,” “Appalachicanos,” the Affrilachian Poets, and the wonderful, brave, progressive youth at the Appalachian Media Institute [AMI] at Appalshop.

In mid-2016 J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy hit bookstores, putting the word and notion of “hillbilly” into the forefront of America’s zeitgeist. And then in early 2016, with the presidential campaign in full swing, we realized we might have to work in the election. By that fall we were nearly done filming, yet we had no narrative “glue” for the film to hold its many ideas and characters together. We decided to insert Ashley and members of her family into the film, as we saw that a microcosm existed in part of her family of what was going on across the country—people finding themselves on opposite sides of the political and cultural aisle from those they love most. Weaving those four disparate threads together effectively into one movie was a huge challenge.

EM: Historically, as you work to show in hillbilly, Appalachian people have been exploited by media representations. Often, this stereotypical representation leads people from the region to be wary and distrustful of media and film. Did you face any opposition while you were filming in Appalachia?

SR: I would say that this was actually one of the easier areas of hillbilly’s production. We certainly had to gain people’s trust—but any filmmaker has to do that, regardless of topic or content. I’ve been making films in the Appalachian region for twenty years, having begun my work there associate producing David Sutherland’s Country Boys, filmed in eastern Kentucky, when I was twenty-one years old. That film [was] broadcast 56 “hillbilly brings new color to the Appalachian community” —LA Film Festival 57 nationally on [PBS’s] Frontline and was seen and appreciated by many folks from Appalachia. I then made my own film in eastern Kentucky, Deep Down (co-directed by Jen Gilomen), which was about mountaintop removal coal mining and gave me a much deeper understanding of the region.

We filmed in the region off and on for three years and worked with many of the folks who appear in hillbilly, including Chad Berry, Silas House, Jason Howard, Lora Smith, and others. When we launched production on hillbilly, our first step was to reach out to many of the folks in the region that I had worked with on Deep Down. Those people knew me, knew my work, and trusted that if nothing else I would bring a level of integrity to a film made in Appalachia. So that helped quite a bit with access, having those previous relationships in place and the endorsements from folks like Chad and Silas who are so respected across the region.

Silas came on as our executive producer and that really helped, plus we very early on added as project advisors many of the most well-respected and trusted Appalachian Studies scholars, such as Barbara Ellen Smith, Emily Satterwhite, Anna Creadick, Meredith McCarroll, Jerry Williamson, Tony Harkins, Kirk Hazen, and also Chad, Silas, and Lora.

EM: The two of you work hard to include diverse voices from Appalachia to combat images of the stereotypical Appalachian. How did you determine who you would feature in the film?

SR: We cast a very wide net with this. We knew we were looking for folks who were doing groundbreaking and innovative cultural work in the region, people like [Affrilachian poets] Frank X Walker and Crystal Good. We came across people all the time that we wanted in the movie, 58 including those who ended up in the movie and many who did not.

But circling back to the diverse voices who were ultimately featured in the movie: one defining factor for who we filmed with and who made the final cut really had to do with the scenes we were able to film. When we found someone who we felt offered something new to the film, we tried to figure out a way to include them in a verite scene rather than simply in an interview. Many of the diverse voices in the movie are featured that way, in a scene actually unfolding rather than talking to camera, and it makes them easier to connect with and more compelling. Along with Crystal and Frank, we filmed with [queer singer-songwriter] Sam Gleaves and friends, Kate Fowler and her crew at AMI, Crystal Wilkinson and [singer-songwriter] Amythyst Kiah and [poet and scholar] Sam Cole, and so many more amazing people doing very important cultural work in the region. Executive producer Silas House was the one who led us to many of these subjects—his assistance in that realm was critical.

EM: Tensions run high in the footage about the 2016 presidential election. How did you balance the two sides represented in the film? Was it difficult to avoid division?

SR: There were several ways we were able to accomplish this. Almost all of the funding for the film came from government grants, both national and state. We received funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts, as well as grants from the humanities councils of Kentucky, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, and Ohio. So while we never gave up any creative control of the film, there was definitely a certain subtle mandate to make a film that would respect the bipartisan views of all 59 Americans, rather than taking just one side. We also grappled in the editing room—a lot—with how partisan to make the film. I believe a film is more effective if it doesn’t take a side, if it asks questions rather than gives answers, if it gets you to think and understand something in a new way. I was very committed to making a movie that didn’t just skewer Donald Trump—plenty of other left-wing media was already doing that. I wanted to make a movie that opened up [an] understanding of a population that so few folks from urban and coastal America know about, and that meant balancing the sides represented in the film. So it wasn’t easy, but it was necessary.

EM: At the end of the film, viewers are left to make up their own minds about the outcome of the election. What feeling are you hoping to leave your viewers with? What do you most want them to take from hillbilly?

SR: It depends on the viewer. I want Appalachian folks to see themselves in these stories, to feel proud of the way they’re represented in the film, to feel like as filmmakers we have honored their stories and accurately represented the impact of the negative media representations on their lives and sense of selves. I want Appalachian folks who watch the film to feel proud of who they are and where they’re from, to feel seen and validated and heard. For viewers from urban areas or areas outside the region, and especially left-wing viewers, I want them to have a new understanding of the Appalachian region. I want their vision of the region to be more complex, more three-dimensional. I want those viewers to be aware of their own complicity in generating and being entertained by those hurtful stereotypes and representations. I want those viewers to learn the impact of those stereotypes, and to think 60 twice now about making a class-based or regional-based slur or joke. I want left-wing audiences to understand the very real, huge, negative political impact of putting Appalachian folks down, negating them time and time again. And I want all viewers, regardless of region or class or political belief, to learn to listen with compassion to people who feel differently than they do.

EM: Your juxtaposition of media stereotypes of Appalachia alongside people who are working to create a more complex representation of the region is a powerful one. What do you think is the power of art in shifting national misconceptions and generalizations about Appalachian people?

SR: I think it depends what kind of art you’re talking about. There’s art that comes from the region, such as the films the young students are producing at AMI. Those young folks are learning how to be creative, how to find their voice, and how to tell their own stories—something so critical, it seems to me, if we are going to focus on changing outside perceptions of the region. Ten there’s the art that comes from outside the region, such as hillbilly, which was produced by folks who have Appalachian connections and roots but are living in Los Angeles. I think and hope that our film can change people’s views, can show the diversity of the alternate, lesser known and more rarely seen Appalachian identities. And I think having Ashley’s story in the film personalizes the film in a way that really resonates for many Americans. The concepts and ideas in the movie become personal. The inclusion of her story brings the ideas in the film from the level of intellect to the level of the heart. It makes the film very impactful for people.

EM: A major conversation right now is how to give Appalachian people a voice to tell their own stories. You do this in hillbilly, and you also show how places like Appalshop are providing narrative spaces for young people in the region. What do you think is the best way to convince the next generation to stay in Appalachia?

SR: Lord, this is a big question, and a difficult one. Programs like AMI are offering young people a chance to create and be heard and to make a difference—without having to leave. We need more programs like that, more that work to uplift young folks from within. People like Lora Smith are doing all sorts of innovative work in the region working with food and farming, promoting the richness of Appalachian culture and encouraging young people to really reclaim it—and to stay. Musicians like Sam Gleaves and Amythyst Kiah are embracing Appalachian music and then “queering” it in their own way, creating traditional music with their own flair. Gifted speakers and writers like Silas House are hugely instrumental in instilling regional pride into young people through their writings and their art, and this gets young folks to stay, certainly. I’ve also heard about the STAY [Stay Together Appalachian Youth] Project, which sounds like it’s doing amazing regional work getting young folks to stay [and] to reinvest in their communities.