2016 was the year of trauma. Prince died. Muhammad Ali…

Keats In Your Time of Pandemic

You remember in Rome you stood in front of a facsimile of a remarkably narrow sleigh bed, a suggestion of the actual bed in which Keats died from consumption when he was twenty-five. What caught your attention were the ceiling carvings over the bed, and you studied them a long while, fascinated by the idea you were looking at one of the last things Keats had seen before dying.

Each square held a carving, a relief of an articulated petaled blossom, a little dome in the center, a pattern repeated again and again, creating a grid. You felt its fine excess.

You’re a poet, that’s what brought you to Keats’s bedside. Now, quarantined at home, isolation your best weapon against the Covid-19 pandemic sweeping across America, you remember walking through the muggy crowded streets in Rome toward the museum next to the Spanish Steps. In your quarantine, you are exhausted by the rage you feel at the utter failure of your government. You want a plan. You want action. You want accountability.

You don’t want to keep coming back to Keats. You don’t want to scuffle again with what the young genius called “negative capability.” But what he’s written keeps surfacing as if it’s your Serenity Prayer: “God give me the grace to ‘live with uncertainties, mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.’” He’s calling for you to live fully within this liminal space, this place of half-knowledge.

The trouble is that Keats’s concept of negative capability is slippery. Each time you believe you can hold onto it, it mutates and becomes something else. Then it dissipates before you. It floats away like something writ on water.

Nevertheless, it’s a beautiful thing. An aesthetic philosophy that dodges and ducks and ultimately throws a knock-out punch to anyone trying to reason out its mysteries. Still you take the punch and get back up. You believe if you could understand more fully what Keats meant by negative capability, you would know how to be here, but also there, and all places in between. You would understand how to keep writing. You want to do as he says, to “let the mind be a thoroughfare for all thoughts,” open yourself freely to move among associations. But America’s pandemic has made a swamp of your mind.

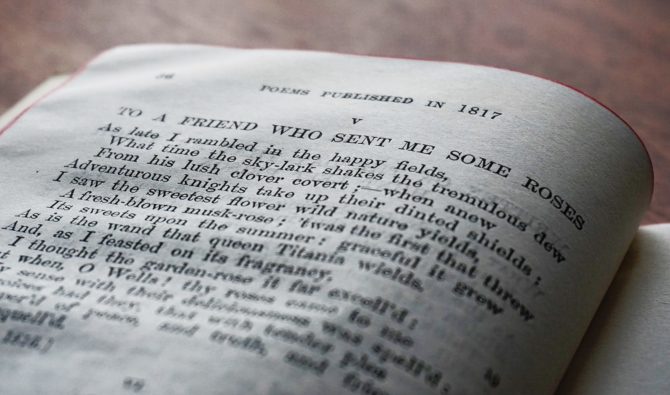

You brought some students with you to the museum. They milled around the rooms, placing their palms on the glass display tables, leaning in to read archival yellowed manuscripts of letters and old books splayed open, revealing Keats’s poems on their brittle pages, while you continued to study the carved ceiling. You’ve somehow always known, even as a child, that the harvest of pattern is surprise. A gift bestowed by turning away from what’s expected. You wonder had Keats lived another year what further would his mind have reaped? Would he have explained negative capability more fully? You wonder if Americans live through this pandemic, who will we be on the other side? How many will be on the other side? What will we understand that we hadn’t before?

The rooms upstairs in the Keats museum are dark but for a ray of glaring sunshine streaming through a window. When you glance back at your students they are shadows surrounded by golden motes in the air around them. You think, well, that’s romantic.

■■■

You have recently entered the demographic who have a higher risk of dying from Covid-19. You reassure yourself that it won’t come for you, not because you’re in tip-top shape, but because you have only very slightly crept over the margin of that age group. Mostly you stay inside, wash your hands, work remotely, wear a mask when on rare occasion you venture out to the grocery or slip back to campus to pick up something you need to plan your hybrid courses for the fall. Covid-19 only slightly ups your thinking about mortality—which is to say you often think about mortality.

You assume most would attribute your “flood subject,” to the fact you’ve lived next to a small graveyard for over twenty-five years. They wouldn’t know, though, that you are taken most with the oldest grave, that of tiny Alpha Beta Blankenbaker, Infant, buried in 1854, the grave closest to you as you fetch the mail at the road. This means the home you live in, which used to be a modest Lutheran church, on the far end of the county where Louisville sits, was built as a complement to the graveyard before the American Civil War, or at least you think that’s what it means.

Keats’s grave in the Protestant cemetery in Rome is not engraved with his name. His friends asked the stonecutter to carve these words on his marker:

This grave contains all that was Mortal of a Young English Poet Who on his Death Bed, in the Bitterness of his Heart at the Malicious Power of his Enemies Desired these Words to be engraven on his Tomb Stone: Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water.

Despite his unmarked grave, Keats lives on but for all you know you’re the only mortal link to Alpha Beta Blankenbaker—and to her aggrieved parents who laid her to rest more than one hundred years before you were born.

Recently, you’ve scanned the headstones for death dates between the fall and winter of 1918-1919, wondering if any one next door died from the Spanish Flu epidemic which began with a local outbreak among soldiers at nearby Camp Zachary Taylor. Then, the virus raged for months and infected nearly 70,000 around Louisville, killing at least 2,000. Kentucky’s governor Andy Beshear announced yesterday our confirmed Covid-19 infections hit 32,298. 804 Kentuckians have died. Thus far. You don’t know why you are trying to make a connection to another historic pandemic, another time. What in the world could it tell you about your own?

You miss your grown children, having them home for long family dinners. They both live in Lexington, an hour away, just far enough so that you have the luxury of missing them while also knowing they can visit often. If you’re lucky, around ten p.m. while still at your table, they will stretch and yawn, and announce they are too tired to drive. You watch them climb the stairs with their beloveds, then hear the doors close behind them in their childhood bedrooms. The next morning, you make coffee for them all and listen to the chatter in the kitchen as your husband cooks breakfast. You hear the toast cheerfully pop up. Then predictably when everyone’s thoughts turn forward, instead of backwards, you wave from the door as they back out of the driveway.

You realize in a few days it will be your daughter’s twenty-fifth birthday. You begin to make plans to celebrate, try to imagine how you can all safely come together, but then remember your son has just had a weekend away fishing and kayaking with the boys and so the dinner plans are put on pause until he has time to quarantine.

Keats, his mother Frances, his brother Tom, all died of tuberculosis, which is also a contagious disease spread via small droplets flung through the air by coughing and sneezing. You think, though, that people seem to live longer with tuberculosis than Covid-19, Keats having first coughed up blood in the summer of 1818 after weeks of strenuous hiking with his friend Charles Armitage Brown through the Lake Country and up into Scotland where they ultimately aimed to visit the Hebrides. Keats died February 23, 1821 in Rome where he’d been sent by his friends so that the harsh English winter didn’t kill him.

You adjust your thinking after counting months on your fingers. Now in the fifth month of your pandemic, with no end in sight, you hope twenty-nine months is not such a long time.

You find yourself in the yard, cleaning the border beds and remember the tree that once stood near. How you were not prepared for the heart-cuts that nicked as you walked into the side yard and noticed the vast absence of the Ash towering fifty feet above in sky-space, then, below—the devastation of the fence, splintered, collapsed, heaped upon itself. It felt like lightning struck in the middle of your chest, first the violent strike, then the numbing, the tingling through your body. You know this feeling because one night when you were twelve lightning struck just outside the window of your bedroom, and its charge passed through the glass pane into you. You lay in bed stunned, watching an electric glow outline your body.

The shuddering grayness of it, what was left of the Ash, the fence, was then punctuated brightly by Mylar balloons tethered to a squat marble headstone, wafting back and forth against their mooring in the light August breeze. By the headstone was a coned bouquet of carnival-colored carnations. You glanced farther and saw Mr. U—rummaging around the back of his pickup parked in the little gravel pad at the far end of the graveyard. You waved to him, only to say a quick hello, but he walked toward you.

“It’s a mess,” you called, as he got closer. You waved your arm down what was once a sturdy barrier of sharp pickets, shattered by the tree surgeon’s miscalculation, and then sat down on one of the many four- to five-foot sections of tree trunk filling the side yard like an archipelago.

“Yep. A real shame,” he agreed, surveying the loss of a 200-year-old tree to the blight of the Borer Beetle which had devastated nearly every Ash tree in Kentucky. He raised his beer can as if to toast you, which seemed odd given the circumstance, but he said, “I’m here to have a birthday drink with my daughter.”

“Oh, I see,” you said, as if you did. After a moment, you asked, “How long has she been gone now? J—?”

At the mention of his daughter’s name, his face brightened, then fell. “Twenty-twelve,” he answered. “And it doesn’t get any easier,” he added, taking in the look on your face, thinking you were thinking that’s a long time.

Five years is a long time, but in fact you were thinking just the opposite. You were thinking how recently it seemed when he, alone, had brought her ashes to the graveyard, how you had been pinning up sheets to dry outside that hot day and watched it all. How he had dug the small hole with a garden trowel, reminding you of the way you had recently planted an Annabelle hydrangea against the fence. And you peered surreptitiously between sheets as he measured the hole against the box of ashes and then, satisfied (though that seems an odd word to use), gently nestled the box into the grave and back-filled the hole with his hands, finally patting it as if his daughter were a small child again, and he were tucking her into a snug bed. And how you thought even with a small grave, there is always dirt left over. A little heap of red clay clods, you thought, as you worked down the clothesline, pinning your clean, damp laundry. You thought of your grandmother’s grave on Black Panther Mountain, the family’s homeplace in West Virginia, but also your other grandmother’s ashes in a box still in your coat closet.

And you were remembering him scooting the small headstone out of the bed of his truck, and then waddling with it across the graveyard, and how you worried about his back, his stance awkward as he wriggled it into place over his daughter’s tiny grave.

How he had been, still sitting near her grave, hours later, when you unpinned the sun-dried sheets. You were not thinking it hasn’t been a long time. What you were thinking was I’m glad I’m not you.

A cable TV show replays video of the mass grave excavated in New York at the height of the city’s Covid-19 spike. A crane dangles a white box in the air, about to lower it next to another and another and another. You realize this pattern can only be broken when the box is isolated, understood to hold the remains of one who lived a singular life, was loved, or not loved, singularly.

In 1818, after turning twenty-one, Keats completely abandoned medical school, though he had already finished a successful apprenticeship as an apothecary-surgeon and was performing surgeries on his own. As he shifted to focus solely on a career as a professional poet, he and Brown traveled by horse and coach from London to Liverpool and commenced by rail, then by foot, to the Lake District to visit Wordsworth at his home, Rydal Mount, where the famous poet had moved his family in 1813 and was to live until he died in 1850. The cottage, also now a museum, is nestled in a beautiful landscape, among lakes and waterfalls, surrounded most immediately by the terraced gardens that Wordsworth himself designed. Notwithstanding the green slick of rhododendron, the sweeping ferns, brilliant pink flox and the periwinkle spires of larkspur framing the panoramic view of rugged Lake Windermere, that’s a long way to go, traveling miles by foot to knock on the cottage door only to find Wordsworth gone, his daughter informing the two men that he was away electioneering for Lord Lonsdale.

Wordsworth had sold out.

That’s slang of your own time but nevertheless a term appropriate to describe how the second coming of Romantic poets, Byron, Shelley, Keats, came to feel about Wordsworth, who had traded in his radical democratic ideals for the job security of tax-collecting for the king. The reputation of Coleridge, Wordsworth’s early writing partner, had fared a little better among the younger Romantics the two men had arguably birthed. Coleridge had taken to publishing conservative diatribes in the London papers, but at least it was rumored that Coleridge had finally come completely unglued, was probably lawfully insane. Wordsworth was still in his right mind.

Admittedly, resentment toward the older poet was slower to build in Keats who had been gobsmacked by an earlier personal introduction to Wordsworth in London when both were invited to dine in the home of the historical painter Benjamin Robert Haydon. Though ultimately Keats came to see Wordsworth as egotistical, he was able to separate his feelings about the man from Wordsworth’s poetry which he held in highest esteem. Keats had inscribed and sent his first book of poems to Wordsworth, hoping the famous poet would open his door wide in welcome and invite Keats and Brown in for tea and also serve up an endorsement of Keats’s poetry. And likely Keats hoped Wordsworth’s positive response to his work would buoy the young poet after a less than spectacular reception of his debut by the newspaper critics. (Little did Keats know he would be completely savaged two months later by the critics in the influential Blackwell’s Edinburgh Magazine, reviews so brutal and personal that Shelley would later claim they had hastened Keats’s death.)

Finding Wordsworth gone, the two young men, disappointed, walked away from the home, where on the south side of the yard Wordsworth would later plant a tribute garden memorializing his daughter, Dora, said to be his favorite child, who died of TB in 1847. She was forty-three.

You imagine Wordsworth dragging a shovel out to those nascent gardens each day until he died. A vision very similar to the one planted in your mind after you, folding warm towels in your laundry room, looked out the window to see two men digging a grave for the son of a neighbor hit by a truck after he had stopped at the side of the road to change a tire for a stranger.

Keats and Brown walked across the Scottish border and through the countryside, staying in small cheap lodgings or in the homes of shepherds, smoky with peat fires, when they could find no proper inn. They visited St. Michael’s Churchyard in Dumfries and stood before the recently erected neo-classical domed mausoleum for Rabbie Burns, which conflicted mightily with Keats’s ideal of Burns as the ploughman farmer poet. Later, Keats and Brown visited the Burns homeplace, a long white thatched cottage in Alloway. One side of the home had housed Burns’s family; the other side provided a stable for the farm animals to shelter in winter, but in 1818 when Keats arrived, the cottage had been converted to a tavern. The young men rested a bit at the bar, toasting the ploughman poet with their whiskys, before trekking on.

They walked through small villages, where women pulled back lace curtains to peek at the strangers plodding by. They were an odd sight. Keats wore a comical fur hat and a tartan cloak over his shoulders for warmth. Brown had had a tailor sew a suit for him especially for the walking tour: a matching jacket and trousers in a bright red tartan meant to honor his Scottish heritage. They slogged through muddy meadows which sucked at their leather boots, soaking their socks and withering the pink flesh on their feet, on the way toward and over the mountains and to the sea.

Keats and Brown hired a boat to sail to Staffa of the Inner Hebrides and climbed in the vessel only large enough to hold the pair and the boat’s pilot, who deftly maneuvered up and down, bucking over sea swells on the short voyage toward Fingal Cave, a towering, glittering cavern lined on either side by basalt columns, “a cathedral in the sea,” Keats called it later in his letters, writing that the water washed in a “lurking gloom of purple.” It impressed Keats beyond measure and was precisely the sort of unfamiliar landscape he wanted to experience and write about in an epic poem he had planned to call “Hyperion,” which he only had time to partially finish after his trip through Scotland.

It is said that Keats ruined his health—he’d already been suffering from a sore throat which grew more painful with each soggy mile—to climb Ben Nevis, the tallest point in Britain, reputed to afford a vista like no other. Though his companion Brown saw that Keats was visibly weakened and footsore, the pair had been walking, mostly in rain, for nearly six weeks by then, Keats insisted they climb the mountain to take in the spectacular views. Once he summited the rocky cap of Ben Nevis, he couldn’t see what he had hoped. A persistent thick mist hung just below the peak and mostly obscured for 360 degrees. His view from the top of Ben Nevis had to be imagined.

On the way down, it was clear to both men then that Keats was too sick to continue with their traveling plans. He and Brown headed back to London. In August, the worst critical attacks would appear in Blackwell’s. The critic John Gibson Lockhart, now really only remembered for his cruel review of Keats’s poetry, wrote this:

We venture to make one small prophecy, that his bookseller will not a second time venture 50 quid upon any thing he can write. It is a better and a wiser thing to be a starved apothecary than a starved poet; so back to the shop Mr John, back to “plasters, pills, and ointment boxes,” &c. But, for Heaven’s sake, young Sangrado, be a little more sparing of extenuatives and soporifics in your practice than you have been in your poetry.

That fall, Keats would nurse his younger brother Tom until his death from tuberculosis on the first of December, but just the next spring Keats wrote what are arguably the best odes in the English language: chiefly among them “Ode to a Grecian Urn,” “Ode to Autumn,” and “Ode to a Nightingale.” At least those are your favorites.

Less than a year later young Keats would also be dead, spirited away through purple gloom.

■■■

Your grandmother had just placed a pot of purple mums on the grave of her old auntie who had died of tuberculosis early in the twentieth century, and then took your hand and led you through the gravestones. You skipped every few steps to keep up, your plaid skirt swishing. You weren’t paying attention to anything but her. In her late forties then, your grandmother was still considered a beauty. You’d even heard your mother—who had a prickly relationship with her mother-in-law—admire the way your grandmother had managed to hang on to her looks, to not let herself go. Always dressed to the nines your mother would say. Always in stockings, fashionable spectator pumps on her feet. She had on those white shoes with black toes and heels as you walked with her over the lawn of the cemetery. Behind, her heels marked a Morse code of indecipherable dots.

Not realizing what the structure was or how incongruously it sat among the gravestones, you broke free and ran toward it. You put your hands to the glass to better see what was inside, to darken your view. In the dollhouse, the marker taller than you were, a poster-bed with linens. Pillows. Tassels hanging from the curtains at the glass windows. A woven rug of blues and greens on the wooden floor, similar to the braided rug under the dining room table at your grandmother’s. You walked around it and around it, your hand trailing the exterior. The peaked shingled roofline twinkled.

It was mysterious.

“The little girl,” your grandmother explained—you looked at your grandmother’s face trying to comprehend what she was telling you. The bright sky hurt your eyes as you looked up. The little girl died when she was five.

“I’m five,” you said.

“Yes, you are,” your grandmother said, leaning over, brushing the bangs out of your eyes. “But she died a long time ago during a dreadful pandemic. You are safe and healthy and alive,” she said. “And you’ve been immunized against measles.”

You wonder if the dollhouse still stands in the middle of that rural cemetery

Still. That word kicks about in your mouth. A word that both you and Keats are fond of thinking about, of using, and which means, of course, to stay, to remain stopped, to discontinue. But looking into its word-heart we know that definition is only a half-knowledge and rests in tension with its other meaning, which calls us to continue, continue, continue. There’s a swift river between you and the other side of this pandemic and the only way to cross, Keats seems to be saying, is to leap from one slick boulder to another, despite being uncertain that you’ll make it to the other side. The way he did when sick and sore in Scotland. That’s negative capability, you think.

Then, it’s all gone.

Again.

Beautiful – thank you !